Government Attacked For AIG Bailout - TIME FOR REFORM!

The Congressional Oversight Panel attacked the Treasury for two aspects of its bailout of AIG.

“By providing a complete rescue that called for no shared sacrifice among AIG's creditors, the Federal Reserve and Treasury fundamentally changed the relationship between the government and the country's most sophisticated financial player.”

“The AIG rescue demonstrated that Treasury and the Federal Reserve would commit taxpayers to pay any price and bear any burden to prevent the collapse of America's largest financial institutions and to assure repayment to the creditors doing business with them.”

The word decapitation can also refer, on occasion, to the removal of the head from a body that is already dead. This might be done to take the head as a trophy , for public display , to make the deceased more difficult to identify, for cryonics or for other reasons.

In an analogous fashion, decapitation can also refer to the removal of a head of an organization. If, for example, the leader of a country were killed, that might be referred to as 'decapitation'. It is also used of a political strategy aimed at unseating high-profile members of a party, as used by the Liberal Democrats in the United Kingdom general election, 2005 .

false claims of unusual exigency - coercive monopoly fraud

INTERVENTION OF RIGHT! NINTH CIRCUIT RULES!

Iron Mountain Mine and T.W. Arman intervene, "two miners"

in looking at the substance of the matter, they can see that it "is a clear, unmistakable infringement of rights secured by the fundamental law." Booth v. Illinois , 184 U.S. 425 , 429 .

"There is no crueler tyranny than that which is exercised under cover of law, and with the colors of justice"

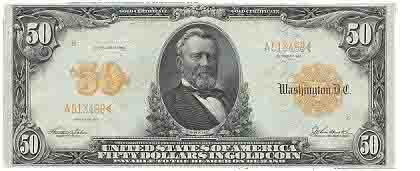

- U.S. v. Jannotti, 673 F.2d 578, 614 (3d Cir. 1982)PUBLIC TRUST LIEN: $137 BILLION AIG OWES THE NATION

CLOSE THE CASINO & ABOLISH SLAVERY - PRICELESS

HOLD OF THE WARDEN - MORMAER OF THE ARMANSHIRE

INSTITUTIONAL SYSTEMIC SOCIOPATHIC FRAUD

T.W. ARMAN FACES EVICTION AS A.I.G. LOOTS BILLIONS

States may make whatever laws they wish (consistent with their State Constitutions) except as prohibited by the US Constitution. Only Laws made by Congress, which are pursuant to the Constitution, qualify as part of the General Government Law of the Land.

This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof … shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding. [emphasis added]

From such a gentle thing, from such a fountain of all delight, my every pain is born.

MichelangeloWords that everyone once used are now obsolete, and so are the men whose names were once on everyone's lips: Camillus, Caeso, Volesus, Dentatus, and to a lesser degree Scipio and Cato, and yes, even Augustus, Hadrian, and Antoninus are less spoken of now than they were in their own days. For all things fade away, become the stuff of legend, and are soon buried in oblivion. Mind you, this is true only for those who blazed once like bright stars in the firmament, but for the rest, as soon as a few clods of earth cover their corpses, they are 'out of sight, out of mind.' In the end, what would you gain from everlasting remembrance? Absolutely nothing. So what is left worth living for? This alone: justice in thought, goodness in action, speech that cannot deceive, and a disposition glad of whatever comes, welcoming it as necessary, as familiar, as flowing from the same source and fountain as yourself. (IV. 33, trans. Scot and David Hicks)

errare humanum est, sed perseverare diabolicum

'to err is human, but to persist is diabolical.'

extra territorium jus dicenti impune non paretur

by Iain Murray June 15, 2010

Conductivity: an inappropriate measure of water quality, says NMA

IM's June article on water management is at deadline for editorial contributions and here we note an interesting opinion from America's National Mining Association. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently issued guidance on water quality requirements for coal mines in Appalachia. The guidance relies solely on electric conductivity (also known as specific conductance) as an indicator of water quality impairment. The guidance establishes a range of between 300-500 microSiemens (a measure of conductivity) as triggering close scrutiny by EPA of the permit application and anything approaching or beyond 500 microSiemens as cause for EPA to deny a Clean Water Act (CWA) permit. These permits are required to operate coal mines and to conduct mine land reclamation in the region. EPA's guidance establishes a de facto water quality standard that interferes with the states' statutory authority to set water quality standards and issue permits. Implementation of the conductivity limit also will make EPA the final decision-maker on permits issued by the US Army Corps of Engineers and the Office of Surface Mining (OSM). The guidance is now open to public comment, but EPA has yet to make the underlying data available for outside peer review or public scrutiny.

Two questions arise from EPA's guidance:

Is conductivity an appropriate measure of water quality impairment? Are the conductivity levels set by EPA defensible or achievable?The answer to both questions is -no.

Conductivity is a measure of a given quantity of water to conduct electricity at a specified temperature. It is predicated upon the presence of dissolved solids, which conduct an electrical charge. It is not a meaningful measure of contamination or the ability of a given body of water to meet its designated use.

Conductivity has generally been used in the field as a first screen for water quality. Elevated conductivity levels indicate that further analysis should be done to determine the specific water chemistry, i.e. the makeup of the specific dissolved particles in the water, and whether those particles occur in amounts that are demonstrated to impair aquatic life specific to that stream. The EPA guidance eliminates this vital step-an approach that is scientifically and legally deficient.

Non-Settling Potentially Responsible Party May Intervene in CERCLA Action

US v. APW N. Am., No. 08-55996 , involved an appeal from the denial of a motion to intervene in an action filed by the EPA under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA). The court of appeals reversed, holding that, under CERCLA, a non-settling potentially responsible party (PRP) may intervene in litigation to oppose a consent decree incorporating a settlement that, if approved, would bar contribution from the settling PRP.

U.S. Supreme Court upholds Kern County ban on L.A. sewage sludge In refusing to review the city's claim, the high court sends the issue back to U.S. District Court for evaluation. The city may re-file in state court. By Louis Sahagun, Los Angeles Times, June 8, 2010

The U.S. Supreme Court's refusal to review Los Angeles' claim that a voter-approved ban on dumping sewage sludge in Kern County violates federal interstate commerce laws has plunged the city into a period of municipal distress over the best way to handle its processed human waste.

The petition aimed to quash a Kern County law known as Measure E, which was approved in 2006 to block shipments from Southern California of more than 450,000 tons a year of treated wastes known as bio-solids to Green Acres, a farm the city bought in 1999 at a cost of about $15 million.

The sludge is tilled into the 4,700-acre farm's soil to fertilize crops, including corn.

The Supreme Court declined to comment last week, letting stand a previous 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decision that the city and its allies, including the Orange County Sanitation District, lacked standing to sue under the commerce clause of the U.S. Constitution because the case involved transfers of a commodity from one portion of the state to another.

The case has been sent back to Los Angeles U.S. District Court Judge Gary A. Feess, who must decide whether to maintain jurisdiction over remaining state-level claims or allow a state court to handle them.

Those claims are that Measure E is preempted by the California Integrated Waste Management Act, which requires local agencies to recycle their wastes, including bio-solids, and that it exceeds its own police powers by exerting authority over another government entity's operations.

Kern County wants Feess to back out of the case, which would require Los Angeles to start all over in state court. Los Angeles would prefer that Feess retain jurisdiction and reaffirm his 2007 ruling that struck down the ban as unconstitutional.

Regardless of Feess' ultimate decision, Edward Jordan, assistant city attorney for Los Angeles, has no intention of dropping his legal challenges against Measure E.

"Our position is that it would be a waste of judicial resources to have this case fully briefed all over again in state court," he said. "But we will re-file in state court if we have to. People have a right to have ballot measures, but local governments cannot go against the State Integrated Waste Management Act."

Kern County officials said the ban was intended to protect underground water and the local environment from possible contamination and emissions from diesel trucks. However, campaign slogans such as "Measure E will stop L.A. from dumping on Kern," and "We've got the bully next door flinging garbage over his fence into our yard" suggested that the law was aimed at slamming the door on Los Angeles' sludge.

In its petition to the Supreme Court, the city warned that the 9th Circuit's decision, coupled with the Kern County ban, could unleash discriminatory trade war restrictions among municipalities in the same state. Blocking the transfer of the sludge would also increase air pollution by causing city trucks to haul the waste hundreds of miles to landfills in Arizona at an annual cost of more than $4 million.

"We've got a $100-million investment in Green Acres," said former Los Angeles Deputy City Atty. Keith Pritsker. "There is no way we are going to walk away from it."

The case is of particular interest to Steve Fan, manager of the 144-acre Hyperion Treatment Plant, the city's oldest and largest wastewater treatment plant.

The plant, just south of Los Angeles International Airport, receives about 350 million gallons of waste water a day via 6,500 miles of sewage lines. The waste is treated with heat and digested by certain strains of bacteria to produce methane gas, which is used to generate electricity and a substance Fan described as "clumpy and very dark with the consistency of wet cake."

"Each day, 28 trucks depart in the early morning — when there is less traffic — with a total 630 tons of wet cake," he said. "By the time it is applied to the land at Green Acres it is a steaming 120 degrees. It meets all state and federal requirements for bacterial counts and heavy metals. The farm is surrounded with a 500-foot-wide buffer zone."

"We really try to be good neighbors there," he said. "The problem is the general concept, perhaps." Third Circuit Clarifies Availability of Cost Recovery Claims Under Section 107 of CERCLA TITLE 5 > PART III > Subpart A > CHAPTER 29 > SUBCHAPTER I > § 2902May 26, 2010 In an April 12, 2010, opinion, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit clarified which claims are available to different classes of potentially responsible parties (PRPs) under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA). In Agere Systems Inc. v. Advanced Environmental Technology Corp ., No. 09-1814, 602 F.3d 204, 2010 WL 1427582 (3d Cir. Apr. 12, 2010), the court denied Section 107 cost recovery claims to PRPs who had been granted contribution protection after settling with EPA or a state, while allowing Section 107 claims by PRPs involved in private party settlements. CERCLA provides PRPs with three potential avenues to recover costs from other PRPs. Under Section 107(a), a party that has incurred costs to clean up a contaminated site may recover those costs from other PRPs. Courts have generally found Section 107 imposes joint and several liability such that the plaintiff could recover 100 percent of its costs from defendants. Defendants in turn could bring contribution claims to defray the potential impact of joint and several liability. Under Section 113(f)(1), a PRP may seek contribution from any other PRP during or following a civil action under Section 106 or 107 of CERCLA. See Cooper Industries, Inc. v. Aviall Services , Inc., 543 U.S. 157 (2004) (denying PRP a contribution action under 113(f)(1) unless it had been sued in a 106 or 107 action). Under Section 113(f)(3)(B), a PRP who has resolved CERCLA liability to a governmental unit through settlement may seek contribution from any other PRP. Courts applying Section 113 allocate response costs among liable PRPs based on their “fair share” using equitable factors. In Agere , five plaintiffs who incurred costs in the cleanup of the Boarhead Farms Superfund Site in Pennsylvania asserted claims under both Sections 107 and 113. One significant benefit that CERCLA gives to PRPs who enter into a settlement with the government is contribution protection — such PRPs are shielded from future contribution liability for the matters addressed in the settlement that might have been brought against them by other PRPs. In the Third Circuit, however, this protection now comes with a price. Shielded PRPs do not have recourse to the potentially higher joint and several recovery provided under 107(a), and must instead rely solely on recovery based on equitable (and several) contribution liability under 113(f). The court based its holding in part on the desire to balance the allocation of cleanup costs. When a plaintiff PRP brings a 107(a) action for complete recovery against a defendant PRP, the defendant generally can file a contribution counterclaim under 113(f)(1). In this way, as recognized by the Supreme Court in United States v. Atlantic Research , 551 U.S. 128 (2007), the defendant can “fend off” the joint and several claim and thereby effectively convert the action to one in contribution where each PRP, including the plaintiff, can be assigned some share of liability. In cases where a PRP has gained contribution protection, however, the Third Circuit found this strategy becomes impossible; the defendant would be barred from bringing any 113(f) contribution counterclaim in response to the 107(a) claim and thus, a shielded plaintiff could potentially recover 100 percent of its costs — including its own share — from the defendant. The Third Circuit found this to be “a perverse result, since a primary goal of CERCLA is to make polluters pay.” Thus, the court denied the 107(a) claims to the PRPs with contribution protection. While the court closed the door of 107(a) availability to one group of PRPs, it opened it to another. Although most of the plaintiffs in this case entered into two consent decrees with the government, Agere Systems Inc. and TI Group Automotive Systems LLC did not. These two did, however, voluntarily enter into private settlement agreements with the other plaintiffs, wherein all the settling parties contributed to a common fund from which the costs of remediation were paid. Section 107(a) permits recovery of costs a party “incurred” in cleaning a site. In Atlantic Research , the Supreme Court found that that this language does not encompass costs paid as a result of a court judgment or settlement agreement payment where such payments are not incurred directly in cleanup activities, but rather reimburse other parties for costs they incurred. Carpenter argued that, because Agere and TI's payments were made in connection with a settlement agreement, they did not qualify for 107(a) recovery. The Court of Appeals disagreed, holding that the Supreme Court's decision was made in a different context and noting the distinction between a settlement agreement which requires a party to reimburse others for past costs incurred and an agreement which requires the party to conduct on-going work and incur its own response costs. In addition, the ordinary meaning of the word “incurred” should include all payments made for on-going work, regardless of whether payments were made into a group trust or directly incurred in cleanup activities. The court seemed particularly concerned that Agere and TI be given adequate opportunities for contribution recovery. These parties were not eligible for 113(f)(1) contribution claims as they were never subject to a civil action under CERCLA. Nor were they eligible for 113(f)(3)(B) contribution claims as they had not “resolved” their liability to any governmental unit. To also deny them a 107(a) claim would act as a complete bar to recourse under CERCLA. This holding, the court said, also encourages PRPs to voluntarily take responsibility for cleanup costs by ensuring that, regardless of government involvement, they will have some cost recovery claim available to them. This decision attempts to resolve questions raised by the recent Supreme Court CERCLA decisions as to when Section 107 or 113 are applicable, and will likely have far-reaching impacts, not the least of which will be felt in bankruptcy proceedings. Bankruptcy Code Section 502(e)(1)(B) mandates disallowance of contingent contribution claims of entities co-liable with the debtor to a third-party creditor. Section 113(f) contribution claims against bankrupt PRPs for their share of future cleanup costs are particularly vulnerable to this provision of the Code. In denying 107(a) direct actions to PRPs who have gained contribution protection through settlements with the government, and limiting such PRPs to contribution claims, the Third Circuit has also significantly limited (if not eliminated) the ability of these PRPs to recover any future costs against a PRP debtor's estate. Courts across the country, including the Supreme Court, have long wrestled with the interplay between 107(a) and 113(f). Though not clear in the statute, it seems increasingly evident that, at least in the Third Circuit, while PRPs are not barred outright from a 107(a) claim, they may not utilize the more generous joint and several liability aspects of 107(a) if the PRP has obtained contribution protection. A question remains, however, as to whether costs incurred “outside” the settlement agreement and, thus, not subject to contribution protection, could be recovered as part of the 113 claim based on that settlement or a 107 claim. The line between 107 and 113 recoverable costs continues to be somewhat muddied as a result of the Supreme Court decisions, and the circuit courts continue to try to define these lines. § 2902. Commission; where recorded (a) Except as provided by subsections (b) and (c) of this section, the Secretary of State shall make out and record, and affix the seal of the United States to, the commission of an officer appointed by the President. The seal of the United States may not be affixed to the commission before the commission has been signed by the President. (b) The commission of an officer in the civil service or uniformed services under the control of the Secretary of Agriculture, the Secretary of Commerce, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of a military department, the Secretary of the Interior, the Secretary of Homeland Security, or the Secretary of the Treasury shall be made out and recorded in the department in which he is to serve under the seal of that department. The departmental seal may not be affixed to the commission before the commission has been signed by the President. (c) The commissions of judicial officers and United States attorneys and marshals, appointed by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, and other commissions which before August 8, 1888, were prepared at the Department of State on the requisition of the Attorney General, shall be made out and recorded in the Department of Justice under the seal of that department and countersigned by the Attorney General. The departmental seal may not be affixed to the commission before the commission has been signed by the President. TITLE 5 App. > FEDERAL > § 2 § 2. Findings and purpose (a) The Congress finds that there are numerous committees, boards, commissions, councils, and similar groups which have been established to advise officers and agencies in the executive branch of the Federal Government and that they are frequently a useful and beneficial means of furnishing expert advice, ideas, and diverse opinions to the Federal Government. (b) The Congress further finds and declares that— (1) the need for many existing advisory committees has not been adequately reviewed: (2) new advisory committees should be established only when they are determined to be essential and their number should be kept to the minimum necessary; (3) advisory committees should be terminated when they are no longer carrying out the purposes for which they were established; (4) standards and uniform procedures should govern the establishment, operation, administration, and duration of advisory committees; (5) the Congress and the public should be kept informed with respect to the number, purpose, membership, activities, and cost of advisory committees; and (6) the function of advisory committees should be advisory only, and that all matters under their consideration should be determined, in accordance with law, by the official, agency, or officer involved. TITLE 5 App. > FEDERAL > § 5 § 5. Responsibilities of Congressional committees; review; guidelines (a) In the exercise of its legislative review function, each standing committee of the Senate and the House of Representatives shall make a continuing review of the activities of each advisory committee under its jurisdiction to determine whether such advisory committee should be abolished or merged with any other advisory committee, whether the responsibilities of such advisory committee should be revised, and whether such advisory committee performs a necessary function not already being performed. Each such standing committee shall take appropriate action to obtain the enactment of legislation necessary to carry out the purpose of this subsection. (b) In considering legislation establishing, or authorizing the establishment of any advisory committee, each standing committee of the Senate and of the House of Representatives shall determine, and report such determination to the Senate or to the House of Representatives, as the case may be, whether the functions of the proposed advisory committee are being or could be performed by one or more agencies or by an advisory committee already in existence, or by enlarging the mandate of an existing advisory committee. Any such legislation shall— (1) contain a clearly defined purpose for the advisory committee; (2) require the membership of the advisory committee to be fairly balanced in terms of the points of view represented and the functions to be performed by the advisory committee; (3) contain appropriate provisions to assure that the advice and recommendations of the advisory committee will not be inappropriately influenced by the appointing authority or by any special interest, but will instead be the result of the advisory committee's independent judgment; (4) contain provisions dealing with authorization of appropriations, the date for submission of reports (if any), the duration of the advisory committee, and the publication of reports and other materials, to the extent that the standing committee determines the provisions of section 10 of this Act to be inadequate; and (5) contain provisions which will assure that the advisory committee will have adequate staff (either supplied by an agency or employed by it), will be provided adequate quarters, and will have funds available to meet its other necessary expenses. (c) To the extent they are applicable, the guidelines set out in subsection (b) of this section shall be followed by the President, agency heads, or other Federal officials in creating an advisory committee. TITLE 5 App. > INSPECTOR > § 2 § 2. Purpose and establishment of Offices of Inspector General; departments and agencies involved In order to create independent and objective units— (1) to conduct and supervise audits and investigations relating to the programs and operations of the establishments listed in section 11 (2) ; (2) to provide leadership and coordination and recommend policies for activities designed (A) to promote economy, efficiency, and effectiveness in the administration of, and (B) to prevent and detect fraud and abuse in, such programs and operations; and (3) to provide a means for keeping the head of the establishment and the Congress fully and currently informed about problems and deficiencies relating to the administration of such programs and operations and the necessity for and progress of corrective action; there is established— (A) in each of such establishments an office of Inspector General, subject to subparagraph (B); and (B) in the establishment of the Department of the Treasury— (i) an Office of Inspector General of the Department of the Treasury; and (ii) an Office of Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration. TITLE 5 App. > INSPECTOR > § 9 § 9. Transfer of functions (a) There shall be transferred— (1) to the Office of Inspector General— (A) of the Department of Agriculture, the offices of that department referred to as the “Office of Investigation” and the “Office of Audit”; (B) of the Department of Commerce, the offices of that department referred to as the “Office of Audits” and the “Investigations and Inspections Staff” and that portion of the office referred to as the “Office of Investigations and Security” which has responsibility for investigation of alleged criminal violations and program abuse; (C) of the Department of Defense, the offices of that department referred to as the “Defense Audit Service” and the “Office of Inspector General, Defense Logistics Agency”, and that portion of the office of that department referred to as the “Defense Investigative Service” which has responsibility for the investigation of alleged criminal violations; (D) of the Department of Education, all functions of the Inspector General of Health, Education, and Welfare or of the Office of Inspector General of Health, Education, and Welfare relating to functions transferred by section 301 of the Department of Education Organization Act [ 20 U.S.C. 3441 ]; (E) of the Department of Energy, the Office of Inspector General (as established by section 208 of the Department of Energy Organization Act); (F) of the Department of Health and Human Services, the Office of Inspector General (as established by title II of Public Law 94–505); (G) of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the office of that department referred to as the “Office of Inspector General”; (H) of the Department of the Interior, the office of that department referred to as the “Office of Audit and Investigation”; (I) of the Department of Justice, the offices of that Department referred to as (i) the “Audit Staff, Justice Management Division”, (ii) the “Policy and Procedures Branch, Office of the Comptroller, Immigration and Naturalization Service”, the “Office of Professional Responsibility, Immigration and Naturalization Service”, and the “Office of Program Inspections, Immigration and Naturalization Service”, (iii) the “Office of Internal Inspection, United States Marshals Service”, (iv) the “Financial Audit Section, Office of Financial Management, Bureau of Prisons” and the “Office of Inspections, Bureau of Prisons”, and (v) from the Drug Enforcement Administration, that portion of the “Office of Inspections” which is engaged in internal audit activities, and that portion of the “Office of Planning and Evaluation” which is engaged in program review activities; (J) of the Department of Labor, the office of that department referred to as the “Office of Special Investigations”; (K) of the Department of Transportation, the offices of that department referred to as the “Office of Investigations and Security” and the “Office of Audit” of the Department, the “Offices of Investigations and Security, Federal Aviation Administration”, and “External Audit Divisions, Federal Aviation Administration”, the “Investigations Division and the External Audit Division of the Office of Program Review and Investigation, Federal Highway Administration”, and the “Office of Program Audits, Urban Mass Transportation Administration”; (L) (i) of the Department of the Treasury, the office of that department referred to as the “Office of Inspector General”, and, notwithstanding any other provision of law, that portion of each of the offices of that department referred to as the “Office of Internal Affairs, Tax and Trade Bureau”, the “Office of Internal Affairs, United States Customs Service”, and the “Office of Inspections, United States Secret Service” which is engaged in internal audit activities; and (ii) of the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, effective 180 days after the date of the enactment of the Internal Revenue Service Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998 [July 22, 1998], the Office of Chief Inspector of the Internal Revenue Service; (M) of the Environmental Protection Agency, the offices of that agency referred to as the “Office of Audit” and the “Security and Inspection Division”; (N) of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the office of that agency referred to as the “Office of Inspector General”; (O) of the General Services Administration, the offices of that agency referred to as the “Office of Audits” and the “Office of Investigations”; (P) of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the offices of that agency referred to as the “Management Audit Office” and the “Office of Inspections and Security”; (Q) of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the office of that commission referred to as the “Office of Inspector and Auditor”; (R) of the Office of Personnel Management, the offices of that agency referred to as the “Office of Inspector General”, the “Insurance Audits Division, Retirement and Insurance Group”, and the “Analysis and Evaluation Division, Administration Group”; (S) of the Railroad Retirement Board, the Office of Inspector General (as established by section 23 of the Railroad Retirement Act of 1974); (T) of the Small Business Administration, the office of that agency referred to as the “Office of Audits and Investigations”; (U) of the Veterans' Administration, the offices of that agency referred to as the “Office of Audits” and the “Office of Investigations”; and [1] (V) of the Corporation for National and Community Service, the Office of Inspector General of ACTION; [1] (W) of the Social Security Administration, the functions of the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services which are transferred to the Social Security Administration by the Social Security Independence and Program Improvements Act of 1994 (other than functions performed pursuant to section 105(a)(2) of such Act), except that such transfers shall be made in accordance with the provisions of such Act and shall not be subject to subsections (b) through (d) of this section; and (2) to the Office of the Inspector General, such other offices or agencies, or functions, powers, or duties thereof, as the head of the establishment involved may determine are properly related to the functions of the Office and would, if so transferred, further the purposes of this Act, except that there shall not be transferred to an Inspector General under paragraph (2) program operating responsibilities. (b) The personnel, assets, liabilities, contracts, property, records, and unexpended balances of appropriations, authorizations, allocations, and other funds employed, held, used, arising from, available or to be made available, of any office or agency the functions, powers, and duties of which are transferred under subsection (a) are hereby transferred to the applicable Office of Inspector General. (c) Personnel transferred pursuant to subsection (b) shall be transferred in accordance with applicable laws and regulations relating to the transfer of functions except that the classification and compensation of such personnel shall not be reduced for one year after such transfer. (d) In any case where all the functions, powers, and duties of any office or agency are transferred pursuant to this subsection, such office or agency shall lapse. Any person who, on the effective date of this Act [Oct. 1, 1978], held a position compensated in accordance with the General Schedule, and who, without a break in service, is appointed in an Office of Inspector General to a position having duties comparable to those performed immediately preceding such appointment shall continue to be compensated in the new position at not less than the rate provided for the previous position, for the duration of service in the new position. TITLE 5 App. > ETHICS > TITLE IV > § 402 Prev | Next § 402. Authority and functions How Current is This? (a) The Director shall provide, in consultation with the Office of Personnel Management, overall direction of executive branch policies related to preventing conflicts of interest on the part of officers and employees of any executive agency, as defined in section 105 of title 5 , United States Code. (b) The responsibilities of the Director shall include— (1) developing, in consultation with the Attorney General and the Office of Personnel Management, rules and regulations to be promulgated by the President or the Director pertaining to conflicts of interest and ethics in the executive branch, including rules and regulations establishing procedures for the filing, review, and public availability of financial statements filed by officers and employees in the executive branch as required by title II of this Act; (2) developing, in consultation with the Attorney General and the Office of Personnel Management, rules and regulations to be promulgated by the President or the Director pertaining to the identification and resolution of conflicts of interest; (3) monitoring and investigating compliance with the public financial disclosure requirements of title II of this Act by officers and employees of the executive branch and executive agency officials responsible for receiving, reviewing, and making available financial statements filed pursuant to such title; (4) conducting a review of financial statements to determine whether such statements reveal possible violations of applicable conflict of interest laws or regulations and recommending appropriate action to correct any conflict of interest or ethical problems revealed by such review; (5) monitoring and investigating individual and agency compliance with any additional financial reporting and internal review requirements established by law for the executive branch; (6) interpreting rules and regulations issued by the President or the Director governing conflict of interest and ethical problems and the filing of financial statements; (7) consulting, when requested, with agency ethics counselors and other responsible officials regarding the resolution of conflict of interest problems in individual cases; (8) establishing a formal advisory opinion service whereby advisory opinions are rendered on matters of general applicability or on important matters of first impression after, to the extent practicable, providing interested parties with an opportunity to transmit written comments with respect to the request for such advisory opinion, and whereby such advisory opinions are compiled, published, and made available to agency ethics counselors and the public; (9) ordering corrective action on the part of agencies and employees which the Director deems necessary; (10) requiring such reports from executive agencies as the Director deems necessary; (11) assisting the Attorney General in evaluating the effectiveness of the conflict of interest laws and in recommending appropriate amendments; (12) evaluating, with the assistance of the Attorney General and the Office of Personnel Management, the need for changes in rules and regulations issued by the Director and the agencies regarding conflict of interest and ethical problems, with a view toward making such rules and regulations consistent with and an effective supplement to the conflict of interest laws; (13) cooperating with the Attorney General in developing an effective system for reporting allegations of violations of the conflict of interest laws to the Attorney General, as required by section 535 of title 28 , United States Code; (14) providing information on and promoting understanding of ethical standards in executive agencies; and (15) developing, in consultation with the Office of Personnel Management, and promulgating such rules and regulations as the Director determines necessary or desirable with respect to the evaluation of any item required to be reported by title II of this Act. (c) In the development of policies, rules, regulations, procedures, and forms to be recommended, authorized, or prescribed by him, the Director shall consult when appropriate with the executive agencies affected and with the Attorney General. (d) (1) The Director shall, by the exercise of any authority otherwise available to the Director under this title, ensure that each executive agency has established written procedures relating to how the agency is to collect, review, evaluate, and, if applicable, make publicly available, financial disclosure statements filed by any of its officers or employees. (2) In carrying out paragraph (1), the Director shall ensure that each agency's procedures are in conformance with all applicable requirements, whether established by law, rule, regulation, or Executive order. (e) In carrying out subsection (b)(10), the Director shall prescribe regulations under which— (1) each executive agency shall be required to submit to the Office an annual report containing— (A) a description and evaluation of the agency's ethics program, including any educational, counseling, or other services provided to officers and employees, in effect during the period covered by the report; and (B) the position title and duties of— (i) each official who was designated by the agency head to have primary responsibility for the administration, coordination, and management of the agency's ethics program during any portion of the period covered by the report; and (ii) each officer or employee who was designated to serve as an alternate to the official having primary responsibility during any portion of such period; and (C) any other information that the Director may require in order to carry out the responsibilities of the Director under this title; and (2) each executive agency shall be required to inform the Director upon referral of any alleged violation of Federal conflict of interest law to the Attorney General pursuant to section 535 of title 28 , United States Code, except that nothing under this paragraph shall require any notification or disclosure which would otherwise be prohibited by law. (f) (1) In carrying out subsection (b)(9) with respect to executive agencies, the Director— (A) may— (i) order specific corrective action on the part of an agency based on the failure of such agency to establish a system for the collection, filing, review, and, when applicable, public inspection of financial disclosure statements, in accordance with applicable requirements, or to modify an existing system in order to meet applicable requirements; or (ii) order specific corrective action involving the establishment or modification of an agency ethics program (other than with respect to any matter under clause (i)) in accordance with applicable requirements; and (B) shall, if an agency has not complied with an order under subparagraph (A) within a reasonable period of time, notify the President and the Congress of the agency's noncompliance in writing (including, with the notification, any written comments which the agency may provide). (2) (A) In carrying out subsection (b)(9) with respect to individual officers and employees— (i) the Director may make such recommendations and provide such advice to such officers and employees as the Director considers necessary to ensure compliance with rules, regulations, and Executive orders relating to conflicts of interest or standards of conduct; (ii) if the Director has reason to believe that an officer or employee is violating, or has violated, any rule, regulation, or Executive order relating to conflicts of interest or standards of conduct, the Director— (I) may recommend to the head of the officer's or employee's agency that such agency head investigate the possible violation and, if the agency head finds such a violation, that such agency head take any appropriate disciplinary action (such as reprimand, suspension, demotion, or dismissal) against the officer or employee, except that, if the officer or employee involved is the agency head, any such recommendation shall instead be submitted to the President; and (II) shall notify the President in writing if the Director determines that the head of an agency has not conducted an investigation pursuant to subclause (I) within a reasonable time after the Director recommends such action; (iii) if the Director finds that an officer or employee is violating any rule, regulation, or Executive order relating to conflicts of interest or standards of conduct, the Director— (I) may order the officer or employee to take specific action (such as divestiture, recusal, or the establishment of a blind trust) to end such violation; and (II) shall, if the officer or employee has not complied with the order under subclause (I) within a reasonable period of time, notify, in writing, the head of the officer's or employee's agency of the officer's or employee's noncompliance, except that, if the officer or employee involved is the agency head, the notification shall instead be submitted to the President; and (iv) if the Director finds that an officer or employee is violating, or has violated, any rule, regulation, or Executive order relating to conflicts of interest or standards of conduct, the Director— (I) may recommend to the head of the officer's or employee's agency that appropriate disciplinary action (such as reprimand, suspension, demotion, or dismissal) be brought against the officer or employee, except that if the officer or employee involved is the agency head, any such recommendations shall instead be submitted to the President; and (II) may notify the President in writing if the Director determines that the head of an agency has not taken appropriate disciplinary action within a reasonable period of time after the Director recommends such action. (B) (i) In order to carry out the Director's duties and responsibilities under subparagraph (A)(iii) or (iv) with respect to individual officers and employees, the Director may conduct investigations and make findings concerning possible violations of any rule, regulation, or Executive order relating to conflicts of interest or standards of conduct applicable to officers and employees of the executive branch. (ii) (I) Subject to clause (iv) of this subparagraph, before any finding is made under subparagraphs (A)(iii) or (iv), the officer or employee involved shall be afforded notification of the alleged violation, and an opportunity to comment, either orally or in writing, on the alleged violation. (II) The Director shall, in accordance with section 553 of title 5 , United States Code, establish procedures for such notification and comment. (iii) Subject to clause (iv) of this subparagraph, before any action is ordered under subparagraph (A)(iii), the officer or employee involved shall be afforded an opportunity for a hearing, if requested by such officer or employee, except that any such hearing shall be conducted on the record. (iv) The procedures described in clauses (ii) and (iii) of this subparagraph do not apply to findings or orders for action made to obtain compliance with the financial disclosure requirements in title 2 [1] of this Act. For those findings and orders, the procedures in section 206 of this Act shall apply. (3) The Director shall send a copy of any order under paragraph (2)(A)(iii) to— (A) the officer or employee who is the subject of such order; and (B) the head of officer's or employee's agency or, if such officer or employee is the agency head, to the President. (4) For purposes of paragraphs (2)(A)(ii), (iii), (iv), and (3)(B), in the case of an officer or employee within an agency which is headed by a board, committee, or other group of individuals (rather than by a single individual), any notification, recommendation, or other matter which would otherwise be sent to an agency head shall instead be sent to the officer's or employee's appointing authority. (5) Nothing in this title shall be considered to allow the Director (or any designee) to make any finding that a provision of title 18, United States Code, or any criminal law of the United States outside of such title, has been or is being violated. (6) Notwithstanding any other provision of law, no record developed pursuant to the authority of this section concerning an investigation of an individual for a violation of any rule, regulation, or Executive order relating to a conflict of interest shall be made available pursuant to section 552 (a)(3) of title 5 , United States Code, unless the request for such information identifies the individual to whom such records relate and the subject matter of any alleged violation to which such records relate, except that nothing in this subsection shall affect the application of the provisions of section 552 (b) of title 5 , United States Code, to any record so identified.

- JUNE 6, 2010, 8:01 P.M. ET

Texas Governor Perry Declares War on the EPA By Hilary Hylton / Austin Monday, Jun. 07, 2010 EPA announces $10 million for Communities to Combat Climate Change WASHINGTON – The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is making available up to $10 million in grants to local governments to establish and carry out initiatives to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Under the Climate Showcase Communities program, EPA expects to award approximately 25 cooperative agreements ranging from $100,000 to $500,000, with approximately five percent of the funds ($500,000) being made available specifically for tribal governments. Local governments, federally recognized Indian tribal governments, and inter-tribal consortia are eligible for grants to create sustainable community actions that can be used elsewhere, generate cost-effective greenhouse gas reductions and improve the environmental, economic, public health, and social conditions in a community. A 50 percent cost share is required for recipients, with the exception of tribal governments and intertribal consortia, which are exempt from matching requirements under this grant. The grant program is administered by EPA's Local Climate and Energy Program, an initiative to assist local and tribal governments to identify, implement, and track policies and programs that reduce greenhouse gas emissions within their operations and surrounding communities. Over the course of the grant program, EPA will offer training and technical support to grant recipients, and share lessons learned with communities across the nation. This is the second round of funding for the Climate Showcase Communities program. Last year, EPA selected 25 projects to receive $10 million in grants. Proposals are due by July 26, 2010, at 4:00 p.m. EDT. Grants are expected to be awarded in February 2011. More information on the grants: http://www.epa.gov/statelocalclimate/local/showcaseFinancial News: At Last, A Victory For Corporate Governance The $35.5 billion bid by Prudential for AIA, the Asian insurance arm of AIG, was controversial from day one. The sheer size of the deal, the way it was sprung on the market, the way it was to be financed and the involvement of the Financial Services Authority all conspired to ensure that this deal would end up being one of the most significant of 2010, no matter what the outcome. In the event, the Pru's decision to abandon the bid--because it was unable either to convince enough of its shareholders that the price was acceptable, or AIA's parent that ... MEDIA MATTERS

Top White House reporter joins leftist group Leaving to 'do Lord's work' after oil spill, 'combat climate change' Posted: June 15, 2010

10:25 pm Eastern

By Chelsea Schilling

© 2010 WorldNetDaily The president of the White House Correspondents' Association – a group that's the subject of a complaint over alleged discrimination at its annual black-tie dinner in Washington – is leaving his post to "perform the Lord's work" and help "combat climate change " through leftist environmental advocacy. WHCA President Ed Chen, correspondent for Bloomberg News, is known for his "greening" of the annual dinner – including having the association buy carbon credits to offset the travels of Jay Leno and President Obama's motorcade. Now he is leaving to become the federal communications director for the one of the world's largest and most influential environmental lobbying groups, Natural Resources Defense Council – an organization he joined in 2006 before taking a job with Bloomberg News in 2007. Politico's Mike Allen obtained the following e-mail by Chen concerning his change of careers : My regret over leaving one of the world's largest – and certainly the most ambitious – news organizations is offset by a sense of urgency in resuming doing the Lord's work, particularly after the BP oil spill. That debacle was a divine signal to redouble my efforts to help clean up the environment, help America kick its petroleum addiction , and help public officials find the wisdom and courage to do the right thing to combat climate change before it's too late. So, I'm returning to the Natural Resources Defense Council (in Washington), soon to be reachable at: EChen(at)nrdc.org. Allen noted, "The ease with which reporters seem able to jump between reporting and advocacy seems to be increasing, and fewer people seem to be surprised or shocked within Beltway circles. Still, it is this ease and comfort that will likely reinforce notions across the country that all journalists are bias[ed] and largely toward Democratic-friendly organizations." The blog Newsbusters noted that Chen is now the 16th major media figure to join the Obama administration or aligned unions and left-wing environmental groups. According to Brent Baker , vice president of research at the Media Research Center, the 15 other figures include the following:

- Teddy Davis: Former deputy political director for ABC News joined the left-leaning Service Employees International Union, or SEIU. The group endorsed Obama and has worked to advance the president's agenda.

- Roberta Baskin: Former senior investigative producer for ABC News' "20/20" and for CBS "48 Hours" chief investigative correspondent left to become senior communications adviser in the Department of Health and Human Service's office of inspector general.

- Warren Bass: A Washington Post deputy editor left to become adviser to U.N. Ambassador Susan Rice.

- Daren Briscoe: Former Washington reporter for Newsweek became deputy associate director of public affairs for the Office of National Drug Control Policy.

- Jay Carney: Former Washington bureau chief for Time magazine who became assistant to the vice president and director of communications for Vice President Joe Biden.

- Teddy Davis: Former ABC News deputy political director who became SEIU assistant director of communications.

- Linda Douglass: ABC News Washington correspondent and former CBS News reporter who became a senior strategist and senior campaign spokesperson for the Obama campaign. She was also assistant secretary for public affairs at the Department of Health and Human Services and a spokesman for Obama's health reform. Douglass left the Obama administration in April.

- Kate Albright-Hanna: Former CNN producer who became "new media" director for the Obama campaign and worked on Obama's transition website.

- Peter Gosselin: Los Angeles Times Washington correspondent who became a speechwriter for Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner.

- Sasha Johnson: CNN political producer who became press secretary at the Department of Transportation.

- Beverley Lumpkin: ABC News Justice Department correspondent who became press secretary at the Justice Department.

- Aneesh Raman: CNN Middle East correspondent who worked for the Obama campaign's communication department.

- Vijay Ravindran: Chief technology officer for Catalist, a voter database provider for the Obama campaign, became chief digital officer and senior vice president of the Washington Post Company.

- Desson Thomson: Former Washington Post film critic became speechwriter for Louis Susman, U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James (Great Britain).

- Rick Weiss: Washington Post science reporter became communications director and senior policy strategist at the White House Office of Science and Technology.

- Jill Zuckman: Chicago Tribune Washington correspondent became director of public affairs for the Department of Transportation.

News of Chen's new position comes just as Obama announced several members of the NRDC and National Geographic Society will serve in a special commission to investigate the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. As WND reported , the NRDC was named in a 2008 investigation as one of several charitable and environmental organizations claiming to be nonpartisan that were suspected of using donations to funnel money to Democratic Party politicians. Sen. James Inhofe, R-Okla., ranking member of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, referred to several charitable and environmental organizations as "wolves dressed in sheep's clothing." "Campaigns to 'save the cuddly animals' or 'protect the ancient forests' are really disguised efforts to raise money for Democratic political campaigns," Inhofe said while speaking on the Senate floor. "Environmental organizations have become experts at duplicitous activity, skirting laws up to the edge of illegality, and burying their political activities under the guise of nonprofit environmental improvement." Inhofe's report focused on organizations such as Greenpeace, the Environmental Defense Fund, the Natural Resources Defense Council, the League of Conservation Voters and the Sierra Club. Discover the Networks noted that NRDC receives financial backing from numerous left-leaning sponsors, including George Soros' Open Society Institute, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the MacArthur Foundation, the New York Times Company Foundation, the Heinz Family Foundation and many others. The group also reports that NRDC received an estimated $2.6 million from the Environmental Protection Agency during the first three years of the George W. Bush administration and subsequently used the money to fund anti-Bush radio ads in battleground states prior to the 2004 election. Daley to feds: 'Go swim in the Potomac' EPA Marks World Environment Day

Marking the culmination of a full 20 years of planning and development, the Bureau of Land Management and its many partners this morning will dedicate the final leg of a trail running the full length of the eastern side of Keswick Reservoir. Open to all non-motorized users — horses, cyclists, trail runners, dog walkers — the single-track dirt trail runs from Keswick Dam Road north above the lake, connecting to an existing network that leads all the way to Shasta Dam. The final stretch isn't quite finished, but another week or so's work will link the trail to the stress-ribbon bridge on the Sacramento River Trail, just downstream from Keswick Dam. With multiple access points, loops, and side routes to waterfalls and overlooks, the Keswick-area trails can accommodate casual morning nature strolls and off-road ultramarathons alike. And they open to recreational users a beautiful stretch of the Sacramento River canyon that, until recently, demanded venturesome bushwhacking. It was in 1990 that the McConnell Foundation first doled out a grant to Shasta County to study converting the old railroad grade on the west side of Keswick Reservoir into a trail. Today that is the nearly fully paved Sacramento River Rail Trail, and the opportunities have grown rich on both sides of the river in what the BLM calls the “Interlakes Special Recreation Management Area.” There have been roadblocks along the way. Toxic old mine sites peppered the area beneath Iron Mountain Mine on Keswick's west shore. Post-Sept. 11, security concerns near Shasta Dam slowed development. And the route includes some private property, whose owners generously opened their land to easements. Through it all, the BLM, local governments and several private foundations toiled steadily toward scratching their vision into the hillsides. It's a tremendous accomplishment that local residents will enjoy for years. Everyone involved deserves our gratitude. And the best way to thank them? Get out and use it. College of the Hummingbird - Center for Health, and the Institute for Liberty & Independence, (CHILI) Our Mission The College of the Hummingbird - Center for Health, and Institute for Liberty & Independence, (CHILI) works side-by-side with the nation's top emergency responders in the public and private sector to develop plans, policies, and strategies that ensure the safety of citizens in the event of natural or man-made catastrophes, (we'll bring the chili) and assure the defence and protection of the consitution. To fulfill that mission, CHILI focuses on general emergency preparedness planning, continuity of operations planning and training, preparation of special needs populations during emergencies, mass evacuation and sheltering planning, emergency communication systems, hospital coordination, table top and field emergency response exercises, the provision of adequate energy supplies during emergencies, and therefore is in need of grant writing assistance for governmental institutions seeking to provide funding for emergency planning efforts and similar needs. Iron Mountain Mine Re-Working Group Open Government & Communities Engagement Initiative Action Plan, June 2010

In December 2009, EPA’s Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response (OSWER) circulated for public comment a draft Proposed Action Plan for its Community Engagement Initiative. EPA received and incorporated public comments on the draft Plan and also developed the OSWER Community Engagement Initiative Iplementation Plan. The Implementation Plan lays out specific actions and activities that EPA will undertake to achieve the goals and objectives of this Action Plan.

The Community Engagement Initiative will enhance EPA’s Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response and regional office engagment with local communities and other stakeholders (e.g., state and local governments, tribes, academia, private industry, other federal agencies, non profit organizations) to help them meaningfully participate in government decisions on land cleanup, emergency preparedness and response, and the management of hazardous substances and waste.

This effort provides an opportunity for OSWER to refocus and renew its vision for community engagement, build on public involvement practices, and apply them consistently in EPA processes. Specifically, the Community Engagement Initiative focuses on taking active measures to reach out to communities and stakeholders, identifying steps EPA will take to engage these communities and stakeholders in the policy development and implementation procsses, and evaluating the effectiveness of changes in processes and procedures.

Basis for Action

The cleanup of contaminated land and pollution and the management of hazardous substances and waste by EPA directly affect communities long after the work is finished. For example, the cleanup of a hazardous waste site involves critical decisions that affect the surrounding communities: What are the potential exposures to the contamination and what are the risks? Who is responsible for the contamination and what government programs are available to oversee the cleanup? Will the cleanup affect adjacent properties? What measures will protect the health and safety of the community during and after the cleanup? Will the cleanup allow for future uses of the site that are consistent with current community goals and plans? What agreements are being made with responsible parties or developers that may affect the community? Who will be responsible for overseeing and maintaining the protectiveness of the remedy (including any institutional controls), and if it is the local community, will they be able and are they willing to meet the responsibilities? Will financial and technical assistance be provided?

Iron Mountain Mine Re-Working Group Community Engagement Initiative –Action Plan

In addition to site specific actions, EPA may also affect communities through its national regulations and policies that affect the management of underground storag tanks, solid waste and hazardous substances, as well as their associated transportation routes and storage facilities. Individual properties, development and land use plans, business operations, local economies, or other vital interests of a community may be affected by EPA regulations and policies.

Guiding Principles

The purpose of this Action Plan is to present guiding principles, goals, and actions to enhance OSWER’s relationships with communities as we carry out our mission to protect human health and the envionment.

Proactively Include Communities in Decision Making Processes: The people who are most affected by EPA decisions should have influence over the outcome. Effective community engagement is about a process of interactions that builds relationships over time and recognizes and emphaizes the community’s role in identifying concerns and participating in formulating solutions. It establishes a framework for collaboration and deliberation. In the broadest sense, community engagement in environmental decision making is the inclusion of the community in the process of defining the problem and developing solutions and alternatives. The level of engagement varies by site and issue. Most models of public involvement in environmental policy making allow for a range of citizen participation and interaction. The level of participation is influenced by access to information, the skills and resources of the community members, degree and frequency of communication, and the nature of the action. The size and makeup of an affected community is often relative to the size and scope of the problem being addressed by the EPAaction – ranging from a few residents living near a remote leaking underground storage tank, to large populations in towns and cities that could potentially be affected by a new regulation. EPA should manage its resources in smart and effective ways to ensure community engagement

Make Decision Making Processes Transparent, Accessible and Understandable, and Include a Diversity of Stakeholders: A transparent, interactive relationship with all stakeholders, especially community stakeholders, must be a fundamental principle of EPA’s cleanup, emergency preparedness and response, and hazardous substances and waste management programs. Transparency and access is essential to meaningful, deliberate and fair stakeholder participation in EPA decision making processes. Community stakeholders should have the opportunity to be engaged early and frequently in decision making processes and have easy access to understandable information that allows them to participate meaningfully. When the decision making process is transparent, includes a diversity of stakeholders, and prepares stakeholders to meaningfully participate, EPA is obligated to 1) substantially consider all stakeholder concerns, and 2) make timely decisions on public health protectiveness and community benefits. OSWER will refocus its efforts to improve its processes to be transparent and accessible, and present environmental information in a variety of forms and through multiple venues so that a diverse community of stakeholders can participate in an informed way, including disadvantaged and at‐risk populations.

Explain Government Roles and Responsibilities: There are usually numerous governmental agencies involved in decision making processes. However, many community members see the various agencies as one entity. For this reason, successful community engagement must be coupled with solid and thoughtful interagency collaboration. OSWER programs should explain exactly what EPA can and cannot do and the roles and responsibilities of other governmental agenies. It is important for community members to understand what role EPA can play and what EPA cannot deliver. Ensure Consistent Participation by Responsible Parties: Given the role of regulated entities and responsible parties in conducting cleanups, EPA must ensure that responsible parties engage community stakeholders in accordance with these principles. Responsible parties conduct and/or fund the great majority of response activities and often work in consultation with EPA personnel on community outreach activties or provide funding to communities to get technical assistance. This is consistent with EPA’s commitment to first require responsible parties to provide funding and conduct site cleanup actiities before using public resources. EPA will continue this practice of overseeing responsible party implementation of community engagement activities.

Goals of this Action Plan EPA invites you to provide input to this Action Plan. This Action Plan is intended to be a working document, and specific actions will be developed and refined with ongoing feedback and input from communities and other stakeholders, local governments, tribes, states, and EPA program offices. When reviewing the proposed actions, please consider the following questions: Are there certain best practices that should be scaled up? Are there specific components of guidance and policy that we should evaluate? Among these actions, which are the highest priority? Are there additional areas on which we should focus? What are the best mechanisms to effectively communicate progress?

This initiative involves EPA programs dealing with brownfields, federal facilities, leaking underground storage tanks, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), enforcement, the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA –Superfund), the Emergency Planning and Community Right to Know Act (EPCRA), and the Clean Air Act Risk Management Program. Many of EPA’s programs are delegated to states and tribes. For those programs, EPA will continue to work closely with states, tribes, and local governments to achieve our shared goals for meaningful and effective community engagement. The results of the Community Engagement Initiative will be evaluated on a regular basis and considered in annual planning procss. The success of the Community Engagement Initiative is strongly dependent on partnerships and effective communication with the ublic and among government agencies.

Iron Mountain Mine Re-Working Group Community Engagement Initiative –Action Plan

OSWER will lead this initiative in coordination with the EPA regions, the Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance (OECA), OECA’s Office of Environmental Justice, and other EPA offices to achieve the following goals:

Goals

I. Develop transparent and accessible decision‐making processes to Enhance meaningful community stakeholder participation

-

Engage stakeholders in the decision making process before it is started

-

To the extent practicable, provide early and frequent opportunities for stakeholders to participate

II. Present information and provide technical assistance in ways that will enable community stakeholders to better understand envirnmental issues and participate in an informed way during the decision making process

III. Produce outcomes that are responsive to stakeholder concerns and are aligned with community needs and long term goals to the extent practicable

-

Enhance EPA’s culture of valuing community perspectives

-

Evaluate and measure the effectiveness of community engagement activities

Objectives and Actions The following objectives listed under each goal1 will be informed and advanced through specific actions conducted by EPA region and OSWER programs in Fiscal Years 2010 and 2011. The actions will lead to improved processes and tools for EPA to work with communities to design specific community engagemen activities and plans. The level of community engagement for any particular site or issue may vary based on the nature of the problem, the make up and needs of the community, and the anticipated scope of site or project work.

Implementation plans and schedules are in development and will identify specific actions and the roles of OSWER programs, regions and other involved EPA offices 1 Goals are mutually supportive, and some objectives overlap among goals. But for clarity, each objective is listed once, under one goal.

2 For example, for Goal 2, Objective 3 – Technical Assistance, OSWER programs will closely review Technical Assistance Grant (TAG) regulations / guidance and other technical assistance processes to determine opportunities to improve them and award technical assistance support to broad and diverse stakeholder groups. And for Objective 5 – Delivery of Information, Regions may look for specific opportunities to pilot new processes and technologies to provide information to at-risk communities near hazardous waste sites. Iron Mountain Mine Re-Working Group Community Engagement Initiative –Action Plan

GOAL 1 DEVELOP TRANSPARENT AND ACCESSIBLE DECISION MAKING PROCESSES TO ENHANCE MEANINGFUL COMMUNITY STAKEHOLDER PARTICIPATION

-

ENGAGE WITH STAKEHOLDERS TO INVOLVE THEM IN DECISION MAKING PROCESSES BEFORE THE PROCESS IS STARTED

-

TO THE EXTENT PRACTICABLE, PROVIDE EARLY AND FREQUENT OPPORTUNITIES FOR STAKEHOLDERS TO MEANINGFULLY PARTICIPATE IN DECISION MAKING PROCESSES

Before starting the decision making process, EPA should make sure the various segments of affected communities are engaged and have an opportunity to be represented in theprocess, especially disadvantaged and at risk populations and work with community stakeholders to:

Conduct a community stakeholder analysis

-

Define the decision making process and determine decision points and schedule

-

Determine forums and opportunities for stakeholder participation

-

Determine what information will be made available for review and when

-

Explain legal and resource issues

OSWER and regions will conduct activities to inform and improve:

Objective 1: Decision making Processes: Identify and revise critical decision making processes, guidance, and rulemaking procedures to support more enhanced, transparent, and upfront collaboration with community stakeholders

Objective 2: Enforcement Processes: Identify and evaluate how enforcement processes can advance the goals of community engagement

GOAL 2 PRESENT INFORMATION AND PROVIDE TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE IN WAYS THAT WILL ENABLE COMMUNITY STAKEHOLDERS TO BETTER UNDERSTAD ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES AND PARTICIPATE IN AN INFORMED WAY DURING THE DECISION MAKING PROCESS

EPA should present complex scientific and technical information so that all members of the community, including at risk and non English speaking populations, can participate in an informed way. EPA should also help communities to easily access electronic information systems. OSWER and regions will conduct activities to inform, improve and develop:

Objective 3: Technical Assistance: Evaluate existing technical assistance processes and pursue specific actions to 1) improve and broaden the availability of technical assistance to communities and 2) enable broad and diverse community representation in decision making processes

Objective 4: Risk Communication: Evaluate and improve risk communication practices and provide cross program training so that hazard information is presented accurately and in ways that are clearly understandable to various commnity stakeholders

Objective 5: Delivery of Information: Evaluate how information is delivered to at‐risk and remote communities and develop options for improvement – to enhance communities’ ability to be informed and meaningfully participate in decision making processes. Issues include: electronic access/digital divide; simplified information; location of information; timely release of information

GOAL 3 PRODUCE OUTCOMES THAT ARE RESPONSIVE TO STAKEHOLDER CONCERNS AND ARE ALIGNED WITH COMMUNITY NEEDS AND LONG TERM GOALS TO THE EXTENT PRACTICABLE

-

ENHANCE EPA’S CULTURE OF VALUING COMMUNITY PERSPECTIVES

-

EVALUATE AND MEASURE THE EFFECTIVENESS OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT ACTIVITIES

EPA programs have a long history of working with communities to achieve successful results. OSWER should build upon good examples of community engagement practices and ensure that key principles are applied effectively and consistently to all critical EPA processes. OSWER should regularly evaluate and, when appropriate, revise its measures and goals for meaningful community engagement. OSWER and regions will conduct activities to inform, improve and develop:

Objective 6: Community Engagement Training: Develop and provide a training program to: 1) strengthen fundamental community engagement skills of key personnel to enable effective community engagement practices and strtegies for projects and sites, and 2) enhance “One site, One team” project management approaches to enable all team members to understand project and community facts, communicate a consistent message to the public and ensure that decisions are based on the results of community consultation Objective 7: Measures: Evaluate and measure the effectiveness of community engagement activities to promote continual improvement and identify needs nd opportunities for future action

Objective 8: Local Workforce Development: Evaluate and promote job training and the use of local labor on environmental projects. This agreement will support collaborative efforts to improve air quality, safe drinking water, management of toxic substances, environmental governance, and water resource management across Iron Mountain Mine, during the time period 2010-2015. The goal of the cooperation is to reinforce owner's rights, miner's rights, resident's rights, other civil rights, and which are now strengthening their environmental laws, ministries, and compliance mechanisms. Cooperation could include technical assistance, training, and joint project development. http://www.usace.army.mil/CECW/Pages/reg_permit.aspxD.C. Circuit questions FERC's jurisdiction